Taxes touch nearly every part of our financial lives. From the paycheck you earn to the stocks or property you sell, governments find different ways to collect revenue. Two of the most common types of taxation that individuals encounter are income tax and capital gains tax. While both reduce your overall earnings, they apply to very different sources of money, and the rules that govern them can affect how much you actually keep.

Understanding the differences between these two tax categories is more than just an academic exercise—it can shape your financial planning, help you make smarter investment decisions, and even lower your yearly tax bill if handled wisely. Let’s take a closer look at what sets them apart, how they are calculated, and why they matter.

The Basics: What Do These Taxes Cover?

At the simplest level, income tax is a levy on the money you earn from work, business activities, or certain investments. Think of it as a tax on wages, salaries, tips, bonuses, freelance payments, and sometimes interest or rental earnings.

Capital gains tax, by contrast, comes into play when you sell something for more than you paid for it. This could be stocks, bonds, real estate, or even collectibles like art or vintage cars. You’re not taxed on the full amount of the sale, but only on the gain—the difference between the purchase price and the selling price.

Both taxes ultimately feed into government revenue, but they operate under very different rules and structures.

How Income Tax Works

The United States uses a progressive income tax system, meaning the more you earn, the higher percentage of your income you pay in taxes. Rates are divided into brackets that range from 10% to 37% at the federal level in 2025. Each portion of your income is taxed at the rate corresponding to its bracket, not all at the top rate you reach.

For example, if you’re single and earn $80,000, part of that income is taxed at 10%, the next chunk at 12%, then 22%, and so on. The higher brackets only apply to the money that falls within their ranges.

In addition to federal income tax, many states impose their own income taxes. Some states have a flat rate where everyone pays the same percentage, while others mirror the federal system with progressive brackets. A handful of states, like Texas and Florida, levy no state income tax at all.

Employers typically handle withholding automatically, deducting estimated income tax from your paycheck. If you’re self-employed, you’re responsible for paying taxes directly through quarterly estimated payments.

Deductions and Credits: Reducing Your Income Tax

One of the most important features of income tax is the ability to reduce what you owe through deductions and credits.

- Deductions lower your taxable income. Examples include contributions to retirement accounts, student loan interest, or mortgage interest.

- Credits reduce your tax bill directly. For example, the Child Tax Credit or education-related credits can cut down the amount you owe dollar-for-dollar.

This is why two people with the same salary can end up with very different tax obligations—their deductions and credits may vary widely.

Capital Gains: Profits from Investments

Capital gains are realized only when you sell an asset. If you own shares of a company and their value rises, you don’t owe taxes until you sell those shares. Once you do, the difference between the selling price and what you originally paid (including fees or commissions) is the taxable amount.

There are two main categories:

- Short-term capital gains – Profits from assets held for one year or less. These are taxed at ordinary income rates, which means they could be as high as 37%, depending on your tax bracket.

- Long-term capital gains – Profits from assets held longer than one year. These enjoy lower rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your taxable income.

This distinction is crucial because it directly affects how much tax you pay. A stock sold after 11 months might cost you significantly more in taxes than the same stock sold after 13 months.

Special Cases and Higher Rates

While most long-term gains fall within the 0–20% range, there are exceptions:

- Collectibles, such as artwork, antiques, or precious metals, can be taxed at a maximum rate of 28%.

- High-income earners may face an additional 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) on top of their regular capital gains tax.

Some states also tax capital gains, often treating them the same way as regular income. That means your location can make a big difference in your overall tax liability.

How to Calculate a Capital Gain

The formula for determining a capital gain is fairly straightforward:

Capital Gain = Selling Price – Cost Basis

The cost basis includes what you originally paid for the asset plus any associated costs, such as broker commissions or fees.

If the result is positive, you owe taxes on that gain. If negative, you have a capital loss, which can actually benefit you. Losses can offset gains, reducing your taxable income. If your losses exceed your gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 of the excess against other income each year, carrying forward any remaining losses into future years.

Comparing Income Tax and Capital Gains Tax

The biggest distinction between these two forms of taxation lies in the source of income and the rates applied.

- Income tax applies to money you earn from work or business, following a progressive bracket system with rates up to 37%.

- Capital gains tax applies to profits from investments, often at much lower rates—especially if you hold assets long-term.

Another difference is timing. Income tax is assessed on earnings as they occur, whether through paycheck withholdings or estimated payments. Capital gains tax, on the other hand, is only triggered when you sell an asset, giving you more control over when you owe taxes.

Strategic Planning for Lower Taxes

Because income tax and capital gains tax operate differently, there are distinct strategies for managing them:

- Income Tax Strategies: Maximize retirement contributions, claim all eligible deductions, and explore tax credits. Timing income is difficult, as it is generally tied to employment.

- Capital Gains Strategies: Choose carefully when to sell assets. Holding for more than a year can dramatically lower the tax rate. You can also harvest losses to offset gains, or donate appreciated assets to charity to avoid tax altogether.

This flexibility often makes capital gains tax easier to manage than income tax, provided you plan ahead.

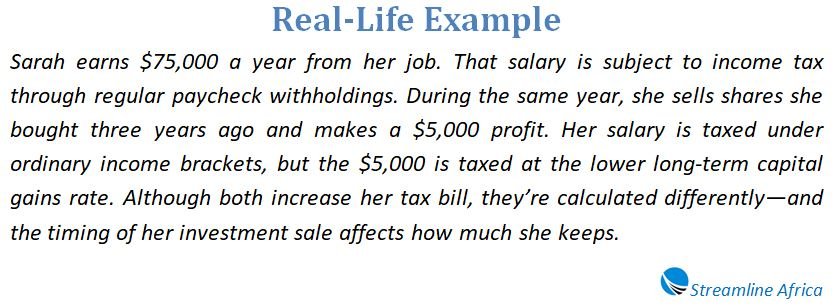

A Practical Example

Imagine you earn $80,000 in salary for the year. That income falls into a tax bracket where part of your wages may be taxed at 22%.

Now suppose you also sell shares in a company and make a profit of $10,000. If you held those shares for longer than one year, the gain would be taxed as a long-term capital gain. At your income level, you’d likely pay 15%, or $1,500, in federal tax on that gain.

If you sold the same shares after just six months, however, the $10,000 would be considered short-term capital gains and taxed at your ordinary rate of 22%. That would cost you $2,200 in taxes—$700 more than if you had simply waited.

This example shows how timing decisions can make a substantial difference.

Why the Distinction Matters

Knowing the difference between income tax and capital gains tax isn’t just about understanding jargon—it’s about financial empowerment. These taxes influence:

- How much money you actually keep after earning or selling.

- When you decide to sell investments, especially in years when your income might be lower.

- How you structure your finances, including retirement contributions, real estate decisions, or charitable giving.

For individuals with investments, the ability to time asset sales is a powerful tool. For workers, using deductions and credits can soften the impact of income tax.

The Role of State Taxes

Federal rules are only part of the picture. Many states impose additional taxes on both income and capital gains. For instance, California taxes capital gains at the same rate as income, which can climb above 13% for high earners. Meanwhile, states like Nevada impose no income or capital gains tax at all.

When planning, it’s essential to consider both federal and state systems, since the combined impact could significantly alter your effective tax rate.

Managing Losses and Offsetting Gains

Capital losses can be just as important as gains. If your investments lose value, those losses can reduce your tax bill. For example, if you made $10,000 on one stock but lost $6,000 on another, you’d only pay tax on the net $4,000 gain.

If your losses are greater than your gains, up to $3,000 can be applied to reduce your taxable income. Any leftover losses can roll into future years until they are fully used.

This strategy, known as tax-loss harvesting, is a common tactic among investors to soften the blow of market downturns.

When to Seek Professional Advice

Tax laws are complex, and the line between income tax and capital gains tax can blur in certain cases. For example, rental income may be taxed as ordinary income, but selling the rental property later can trigger capital gains. Retirement account withdrawals also come with unique rules that mix elements of both tax categories.

Because of these complexities, consulting a tax professional can be invaluable. A qualified advisor can help you minimize liabilities, comply with laws, and align your tax strategy with your overall financial goals.

The Bottom Line

Both income tax and capital gains tax shape how much of your money you ultimately keep. Income tax is largely tied to employment and comes with fewer opportunities to maneuver, while capital gains tax offers more room for planning—especially if you’re willing to hold investments long-term.

By understanding the differences, leveraging deductions and credits, and making informed choices about when to sell assets, you can significantly reduce your tax burden. Taxes may be unavoidable, but with the right knowledge, you can approach them strategically rather than reactively.

When uncertainty arises, a professional tax advisor can ensure your decisions align with both the law and your financial future. In the end, knowing how these two tax systems work empowers you to keep more of what you earn—and what you invest.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is income tax the same as capital gains tax?

No. Income tax applies to wages, salaries, and business earnings, while capital gains tax applies to profits made from selling assets like stocks or property.

Do I pay both income tax and capital gains tax in the same year?

Yes, you may pay both if you earned wages and also sold assets for a profit. They are calculated separately but contribute to your overall tax bill.

How are short-term and long-term capital gains different?

Short-term gains (assets held for one year or less) are taxed like regular income. Long-term gains (assets held for more than a year) benefit from lower, preferential rates.

Can capital losses reduce my taxes?

Yes. Capital losses can offset gains dollar for dollar, and up to $3,000 of excess losses can reduce taxable income each year. Unused losses can be carried forward.

Why are long-term capital gains taxed at lower rates?

Lower rates encourage long-term investment and market stability by rewarding investors who hold assets longer instead of engaging in quick speculation.

How do states handle capital gains tax?

It varies. Some states treat capital gains as regular income, while others have different rules or exemptions. Your location plays a big role in what you owe.

Do I owe tax every year on investments?

No. You only owe capital gains tax when you sell an asset. As long as you hold it, gains are “unrealized” and not taxable.

Can retirement accounts reduce capital gains taxes?

Yes. Investments inside IRAs and 401(k)s grow tax-free until withdrawal, which means you don’t pay capital gains tax as long as they stay in the account.

Does capital gains tax affect selling my house?

Possibly. If the home was your primary residence for at least two of the last five years, you may exclude up to $250,000 ($500,000 for couples) of profit from taxes.

Which is worse: income tax or capital gains tax?

Neither is inherently worse—it depends on your situation. However, capital gains tax often results in a lower rate, especially if you hold assets long term.