In economics, most goods follow a simple principle: when prices go up, people buy less; when prices fall, they buy more. Giffen goods, however, defy this rule. Named after the 19th-century Scottish economist Sir Robert Giffen, these goods behave in a way that seems counterintuitive—demand actually increases when their prices rise. They are usually everyday necessities, not luxuries, and they typically exist in environments where people have limited alternatives to choose from.

Classic examples include staple foods such as bread, rice, and wheat. These are basic items consumed by low-income households, where even small changes in price significantly affect how people spend their money. Unlike luxury products that gain appeal because of their high price tags, Giffen goods are consumed more simply because higher prices alter how households manage their limited budgets.

How Giffen Goods Break the Law of Demand

The law of demand suggests a downward relationship between price and quantity demanded. Yet with Giffen goods, this law does not hold. To understand why, economists focus on two important forces: the income effect and the substitution effect.

When the price of a good rises, the substitution effect normally pushes consumers to look for cheaper alternatives. But in the case of Giffen goods, alternatives are either unavailable or not affordable. At the same time, the income effect comes into play. A rise in the price of a staple food reduces the household’s purchasing power, leaving less money for other foods like meat or vegetables. As a result, families may consume even more of the staple because it is still the cheapest way to meet their basic calorie needs.

This interplay creates an unusual upward-sloping demand curve, making Giffen goods one of the rare exceptions in economic theory.

Why Giffen Goods Are Rare

Economists emphasize that Giffen goods are not commonly found in markets. Most products, even essential ones, tend to follow the traditional demand curve. The special conditions required—low-income households, few substitutes, and staple necessity—make genuine Giffen goods difficult to observe in practice.

Still, their existence is important for understanding human behavior in constrained economic settings. They highlight how poverty and necessity can shape choices that seem irrational when judged against standard economic theory but make sense when viewed in context.

Early Observations in Economics

The idea of Giffen goods gained attention in the late 19th century. Alfred Marshall, a well-known economist, referred to Giffen’s observation that poor households in England sometimes bought more bread when its price rose. The logic was that rising bread prices left families unable to afford other foods, such as meat, forcing them to allocate more of their limited income to bread.

However, not everyone agreed with this reasoning. In 1947, economist George J. Stigler questioned the bread-and-meat example, suggesting the evidence was not strong enough to prove the existence of Giffen goods. This skepticism kept the concept in the realm of theory for many years.

Modern Evidence: Case Studies in China

The debate shifted in the 21st century when Harvard economists Robert Jensen and Nolan Miller conducted an experimental study in rural China. They focused on two provinces: Hunan, where rice was the staple, and Gansu, where wheat dominated diets. By providing households with food vouchers that lowered the cost of these staples, they could observe real behavior changes.

The results were striking. In Hunan, lowering the price of rice actually reduced its demand. When rice became cheaper, families used their savings to diversify their diets with other foods. When the subsidy was removed and rice prices rose again, households consumed more rice because it remained their most affordable option. This confirmed rice as a clear example of a Giffen good.

In contrast, the evidence for wheat in Gansu was weaker. Although wheat was essential, the conditions were not as pronounced, showing that Giffen goods depend heavily on local circumstances.

The Mechanics Behind the Paradox

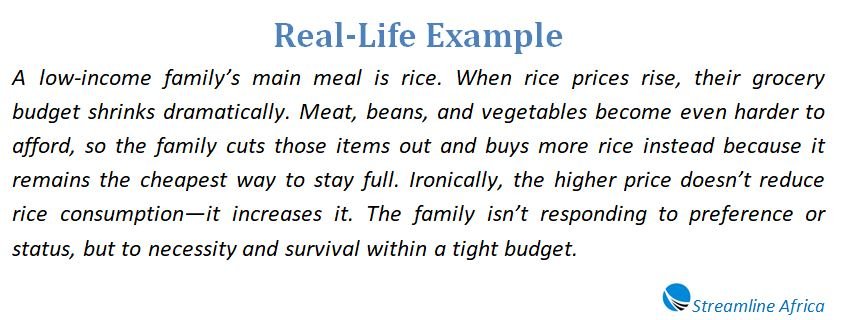

To better understand why this happens, it helps to break down the behavior into everyday terms. Imagine a family living on a tight budget where bread is their staple. If bread prices climb, they may no longer afford other foods like eggs or fish. Instead of replacing bread with another option, they buy even more bread because it still fills their stomachs at a lower cost than alternatives.

The paradox lies in the fact that while price increases normally reduce consumption, in this situation, the need to survive forces people to double down on the staple food. Poverty and limited choices are the key conditions that allow Giffen goods to emerge.

Comparing Giffen Goods to Veblen Goods

At first glance, Giffen goods might be confused with another unusual category: Veblen goods. Both types have upward-sloping demand curves, but the reasons behind them differ dramatically.

Veblen goods, named after economist Thorstein Veblen, are luxury items where higher prices make them more desirable. Think of designer handbags, fine wines, or exclusive watches. For wealthy consumers, the high cost signals prestige, and demand rises as prices climb.

By contrast, Giffen goods have nothing to do with status or luxury. They are consumed more because households are trapped by income constraints and lack of alternatives. In short, Giffen goods are about survival, while Veblen goods are about social status.

Why Giffen Goods Matter in Economics

Although rare, Giffen goods play an important role in economic thought. They remind us that not all consumer behavior can be explained by simple rules. Poverty, necessity, and the absence of substitutes create environments where people act differently from what models predict.

For policymakers, the lesson is significant. Efforts to subsidize food prices, for example, must be carefully designed. Lowering the price of a staple may not always lead to increased consumption of that staple. Instead, households may shift spending to improve their diets in other ways, as seen in the Chinese rice experiment.

Broader Implications for Market Behavior

Understanding Giffen goods helps economists and governments grasp how low-income communities react to price changes. This insight is especially relevant for food security programs in developing nations. When staples dominate diets, price shifts can trigger unexpected changes in demand, potentially worsening food scarcity if not managed properly.

In addition, the concept illustrates how economic theory must adapt to real-world complexity. It shows that demand curves, while useful, are not universal laws but models that sometimes fail under special conditions.

Conclusion: A Rare but Vital Phenomenon

Giffen goods may be uncommon, but they capture an essential truth about economics: human behavior is shaped by necessity as much as by choice. They exist at the intersection of poverty, essential consumption, and limited alternatives, producing outcomes that challenge traditional theory.

From the early debates about bread in 19th-century Britain to the field studies on rice in modern China, the idea of Giffen goods continues to fascinate economists. They remind us that economics is not only about abstract graphs and theories but also about the lived realities of people making difficult decisions under pressure.