The law of diminishing marginal productivity is a principle in economics and management that explains what happens when businesses keep adding more of one resource—such as workers, raw materials, or hours of machine use—while keeping other factors constant. At first, output rises significantly. However, after a certain point, each additional unit of input contributes less to overall production. Eventually, output growth slows down, levels off, or may even decline.

This concept is essential because it demonstrates the limits of simply increasing resources without considering efficiency. It highlights that more is not always better, especially when resources are not perfectly balanced. Managers use this principle to figure out the point at which adding inputs no longer creates meaningful gains and may start to reduce overall effectiveness.

Why It Matters in Business and Economics

The law has direct implications for cost management, pricing strategies, and long-term growth planning. If companies continually increase inputs without understanding when returns start to diminish, they may waste money and resources. On the other hand, knowing where diminishing returns begin helps managers allocate labor, equipment, and capital more effectively.

This principle also complements other economic ideas such as marginal utility—the decreasing satisfaction from consuming additional units of the same good—and economies of scale, where initial efficiency gains eventually transition into inefficiencies. Together, these theories provide a clearer picture of how production systems work in the real world.

The Relationship Between Inputs and Outputs

In simple terms, marginal productivity refers to the extra output gained from adding one more unit of input. For example, if hiring an additional worker increases production by ten units, that is the marginal product of labor. According to the law of diminishing marginal productivity, the next worker may only add eight units, and the one after that six units.

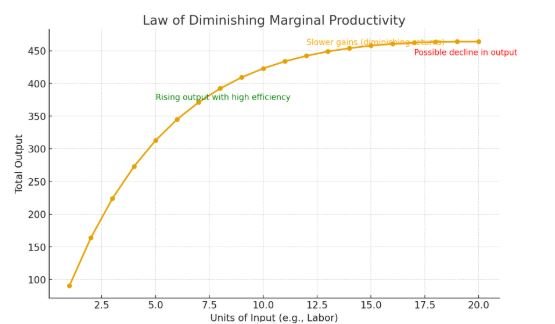

This decline happens because fixed resources—like machinery, land, or space—eventually become overutilized. When too many workers share the same limited resources, productivity falls. Graphically, total output continues to rise, but at a slower rate. The curve flattens until it reaches a maximum point, after which output can decline if input increases further.

Simple Illustrations of the Concept

Agriculture provides one of the clearest examples. Imagine a farmer applying fertilizer to a cornfield. The first application improves yields dramatically. The second still helps but to a lesser degree. After several applications, additional fertilizer adds almost no value, and beyond a certain point, it may even harm the soil and reduce crop output.

The retail industry offers another example. A store facing heavy customer traffic might add employees to handle the rush. Initially, sales improve because shoppers are served more quickly. However, once staffing reaches an optimal level, adding more workers may lead to overcrowding, inefficiency, and even lower sales as employees get in each other’s way.

In manufacturing, similar patterns emerge. A factory producing cars may initially benefit from hiring more workers or running machines longer. Over time, bottlenecks form—too many people competing for limited equipment or space—resulting in lower marginal productivity per worker or per hour of machine use.

The Practical Value for Managers

For decision-makers, understanding diminishing marginal productivity is not just theoretical—it’s a guide to practical choices. It helps identify the optimal level of input where profits are maximized. Beyond that point, costs rise faster than revenue, making expansion counterproductive.

Managers use this insight when planning workforce schedules, budgeting resources, or determining how much inventory or raw material to purchase. For example, scheduling too many employees during slow business hours only increases labor costs without improving sales. Similarly, investing heavily in machinery without balancing labor capacity may create idle resources and reduce efficiency.

Connection to Economies of Scale

Economies of scale describe how businesses initially reduce per-unit costs by producing in larger quantities. Bulk purchasing of raw materials, spreading fixed costs over more units, and streamlined processes often lower costs in the early stages of growth.

However, economies of scale have limits. As companies continue to expand, they encounter diminishing marginal productivity. This means that while overall production may grow, the cost savings per unit become smaller. Eventually, diseconomies of scale may occur—where inefficiencies, mismanagement, or logistical problems increase costs rather than reduce them.

For example, a large factory may benefit from buying raw materials cheaply and producing goods quickly. But once it grows too large, communication breakdowns, overcrowded facilities, or overextended management can cause output per worker to fall, raising costs instead of lowering them.

Quantifying Marginal Productivity

One of the reasons the law is widely studied is that it can often be measured with relative ease. Businesses track marginal productivity by comparing changes in output against changes in input. For example, if a factory produces 100 units with ten workers and 120 units with eleven workers, the additional worker’s marginal product is 20 units.

As more workers are added, the additional output typically shrinks. At some point, the marginal product may become zero or negative, meaning the extra worker adds nothing or reduces overall output. These calculations guide businesses in making rational production decisions.

Costs and Profitability Implications

The law of diminishing marginal productivity directly affects profitability. When inputs initially increase, costs per unit of output fall because the additional resources are used efficiently. But once diminishing returns set in, costs rise faster than output, squeezing profit margins.

For instance, in automobile manufacturing, hiring more labor may initially reduce the cost of producing each car. Over time, however, each new worker contributes less to overall output, increasing the labor cost per car. Managers must recognize when the marginal benefit of adding labor no longer outweighs the marginal cost.

The Threshold Effect in Real Life

One of the most important takeaways is that every production system has a threshold where inputs are optimized. Before reaching it, adding resources boosts efficiency. Beyond it, the returns diminish and can turn negative. Identifying this point requires careful analysis of production data, costs, and outputs.

Farmers, retailers, manufacturers, and service providers alike face this balancing act. Whether it is adding fertilizer, staffing, machines, or marketing spend, the principle remains the same: past a certain level, more resources no longer create more value.

Final Thoughts

The law of diminishing marginal productivity is a reminder of the natural limits within production systems. While adding inputs can boost output, those gains are not infinite. At some point, efficiency declines, costs rise, and returns diminish.

For businesses, this principle emphasizes the importance of balance. Growth and expansion must be managed carefully to avoid inefficiencies. When understood and applied wisely, the law of diminishing marginal productivity helps managers find the sweet spot—where inputs are used most effectively, profits are maximized, and waste is minimized.

Key Facts about the Law of Diminishing Marginal Productivity

Explains the limits of adding inputs

The law shows that continuously adding resources like labor or materials eventually leads to smaller gains in output.

Helps managers optimize resources

It guides decision-makers on when adding more inputs stops being cost-effective and may even reduce efficiency.

Connects to marginal productivity

Marginal productivity measures the extra output from each added input, which gradually declines as more are added.

Illustrated in real-world industries

Examples include fertilizer use in farming, extra retail staff during peak hours, and adding labor in factories.

Closely linked to economies of scale

While producing in bulk can reduce costs initially, diminishing returns set in as inputs become overused.

Shows the importance of thresholds

Every system has a point where input levels are optimal; beyond this, efficiency and profitability drop.

Quantifiable with data

Businesses can calculate diminishing marginal productivity by measuring changes in output against added inputs.

Affects costs and profits directly

Once diminishing returns begin, production costs rise faster than output, narrowing profit margins.