In economic terms, products don’t exist in isolation. The price of one item can often influence how much we buy of another. That’s the central idea behind a concept known as cross price elasticity—a tool economists and businesses use to explore the interconnected nature of consumer choices. Whether it’s burgers and buns, or two rival soda brands, cross price elasticity helps us understand how a shift in one price impacts demand elsewhere.

What Is Cross Price Elasticity?

Cross price elasticity, also called cross elasticity of demand, is a measure that indicates how the demand for one product changes in response to a price change in another. If two goods are linked—either as alternatives or as items typically used together—then changes in the price of one often ripple into the other’s demand.

This concept allows economists to categorize relationships between goods: whether they act as substitutes, complements, or have no connection at all.

How It Works in Practice

Let’s say the price of a popular brand of peanut butter suddenly jumps. Consumers who still want peanut butter may now look to cheaper alternatives—triggering a rise in demand for those competitors. This situation is a textbook example of a positive cross price elasticity, because the increase in one price leads to an increase in demand for another.

Now imagine the price of laptops rises. As a result, fewer people are buying laptops—so there’s also a drop in purchases of laptop accessories like protective cases or chargers. In this case, the products are complementary, and the cross price elasticity is negative.

If two items are unrelated—say, the price of onions and the demand for umbrellas—then we can expect no correlation. The elasticity value hovers near zero in such cases.

The Cross Price Elasticity Formula

To calculate the cross price elasticity between two goods, economists use this formula:

Cross Price Elasticity (Exy) = (Percentage Change in Quantity Demanded of Product X) ÷ (Percentage Change in Price of Product Y)

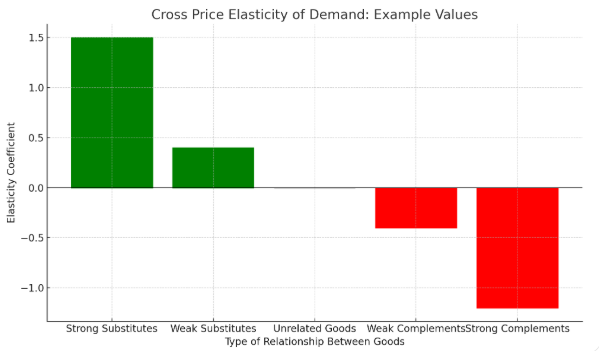

This formula lets analysts quantify the sensitivity of demand for one item in relation to price changes of another. The resulting value reveals the nature of the relationship:

- Positive result: Substitutes

- Negative result: Complements

- Zero or near-zero: Unrelated items

Substitutes: Goods That Compete

Products that can replace each other—like different brands of soft drinks or smartphones—are known as substitute goods. When the price of one rises, consumers tend to shift to the other, leading to a rise in demand for the lower-priced option.

Let’s say the cost of a particular mobile phone brand increases by 10%. If buyers then turn to a competitor offering similar features at a lower price, and its sales go up by 5%, the cross price elasticity would be +0.5. The positive number shows these goods are viewed as interchangeable, though not perfectly so.

The closer the goods mimic each other, the stronger the positive elasticity. A generic cola and a well-known brand, for instance, might show a modest substitution effect. But two brands of virtually identical green tea might have a much higher cross elasticity because consumers are quick to switch when prices vary even slightly.

Complements: Items That Go Hand in Hand

Complementary goods are typically used together. A change in one product’s price can directly impact the demand for its counterpart. Consider examples like bicycles and helmets, or cameras and memory cards. If the price of bicycles rises, fewer people may buy them—and consequently, demand for helmets drops too.

This kind of relationship produces a negative elasticity value. For example, if a 10% increase in coffee prices causes a 3% drop in sugar demand, the cross price elasticity is -0.3. That negative result signifies the connection between the two goods: as one becomes more expensive, fewer people buy the other.

Calculating Cross Price Elasticity: A Step-by-Step Guide

To apply this concept in real-world analysis, here’s a simplified way to calculate cross price elasticity:

- Find the initial and final demand levels for Product X (the good whose demand is changing).

- Note the initial and final prices of Product Y (the related good).

- Calculate the percentage change in demand:

(New Quantity – Old Quantity) ÷ Average Quantity - Calculate the percentage change in price:

(New Price – Old Price) ÷ Average Price - Divide the demand change by the price change to find cross price elasticity.

This method provides a snapshot of how sensitive customers are to price differences among related goods.

Business Strategy and Pricing Decisions

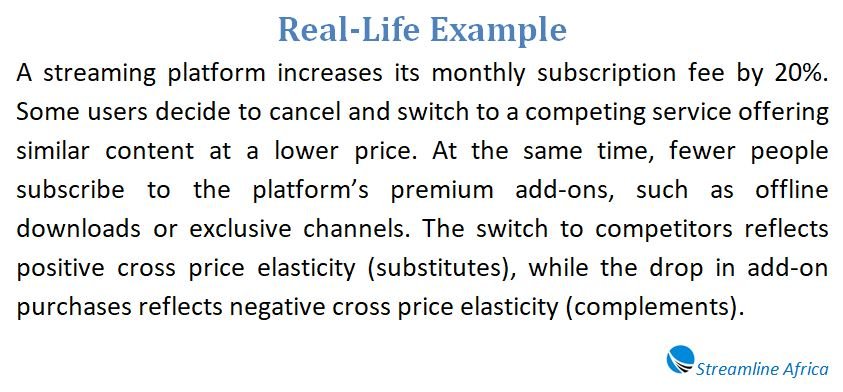

Companies often use cross price elasticity to inform their pricing models. If a business knows that its product has strong substitutes, it may hesitate to raise prices sharply, fearing customers will defect to cheaper competitors. On the other hand, if a company sells a product with few alternatives, it may have more flexibility to adjust prices without significant changes in demand.

The strategy shifts when it comes to complementary goods. A manufacturer might price one item attractively to drive sales of another. A classic example is selling printers at a discount, knowing that consumers will later spend money on ink cartridges, which have higher margins.

Real-World Scenarios

To better understand this concept, let’s walk through a few relatable examples.

Scenario 1: Substitutes

Imagine two local eateries both sell similar chicken wraps for $6. If one restaurant raises its price to $8, many customers might start frequenting the competitor. As a result, the second eatery sees a noticeable uptick in sales—this is cross price elasticity in action.

Scenario 2: Complements

Now think of a combo meal at a fast-food place: a burger and fries. If the burger’s price drops due to a promotion, more people might order it—and many will add fries to their meal. Even though the price of fries hasn’t changed, their demand increases because they’re typically enjoyed together.

Everyday Decisions Reflect Cross Elasticity

You may not think about economics when you shop or eat out, but your decisions often reflect cross price elasticity. If your favorite coffee brand raises prices, you might buy tea instead. Or you might skip ordering dessert if your entrée costs more than usual. Even though you’re not crunching numbers, you’re acting based on the principle.

Simplifying the Concept

Here’s a child-friendly version: Imagine your toy store increases the price of toy cars. So, you decide to buy action figures instead. That’s cross price elasticity—what you buy changes depending on how much other things cost.

Or imagine popcorn and movies. If movie tickets get pricier, you might go to the cinema less often—and that means buying less popcorn too. These everyday shifts reveal how prices influence related choices.

Positive vs Negative Elasticity: What Do They Mean?

A positive value signals a substitute relationship. Think of almond milk versus cow’s milk. If the price of one increases, more people might choose the other.

A negative value indicates complementary behavior. Printers and ink cartridges fall into this group—fewer printers sold usually means fewer cartridges sold, too.

Comparing Related Concepts

Cross price elasticity shouldn’t be confused with regular demand elasticity. The latter measures how demand changes for one product in response to its own price changes. Cross price elasticity, on the other hand, links the price of one good with demand for another.

Similarly, the cross elasticity of supply addresses how much producers adjust output of one product based on price changes in another—more relevant for businesses responding to market shifts, rather than consumers.

Take-Home

Understanding cross price elasticity can offer valuable insight into both business strategy and consumer behavior. From determining the impact of price hikes to planning product bundles or promotions, this economic tool helps forecast how choices ripple through a market.

While you may not calculate elasticity in your daily life, your buying habits often follow its patterns. Whether switching brands or adjusting your shopping cart based on deals, your behavior contributes to the invisible equations guiding modern commerce.

Frequently Asked Questions about Cross Price Elasticity

How do substitute goods behave in cross price elasticity?

If two goods are substitutes, like tea and coffee, a price increase in one leads to a rise in demand for the other. The elasticity value is positive.

What does a negative cross price elasticity mean?

That means the products are complements. When the price of one goes up, the demand for the other falls. Think of items like printers and ink.

Can two unrelated products have cross price elasticity?

No, not really. If the goods have no connection—like eggs and flip-flops—the elasticity is zero because a price change in one doesn’t affect the other.

Why is this concept useful for businesses?

It helps companies make smart pricing decisions. For example, they may lower the price of one product to boost sales of another related item.

What’s a real-life example of substitutes and cross elasticity?

If your favorite brand of cereal gets expensive, you might buy a cheaper brand instead. That switch in demand is cross price elasticity at work.

How do you calculate cross price elasticity?

Divide the percentage change in demand for Product X by the percentage change in price of Product Y. The result tells you the relationship between the two.

Do consumers think about cross price elasticity?

Not directly, but they respond to it all the time—by swapping products or skipping items depending on what’s affordable or on sale.

What’s the difference between cross price elasticity and demand elasticity?

Cross price elasticity involves two products and how they interact. Demand elasticity looks at how one product’s demand changes with its own price changes.

How does this apply in your daily life?

Every time you choose one product over another because of price—or avoid a combo purchase because something got pricier—you’re showing cross price elasticity in action.