What the Investment Multiplier Means

The investment multiplier is a powerful idea in economics that helps explain how new investments, whether by governments or private businesses, can influence the entire economy. It is rooted in the work of John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century. According to this concept, an initial injection of spending does not stop at its first impact. Instead, it sets off a chain reaction where income and consumption expand far beyond the original investment.

At its core, the multiplier shows how money circulates through an economy. When someone receives income, they spend a portion of it on goods and services. The recipients of that spending then do the same, continuing the cycle. Because of this repeating process, the overall boost to the economy becomes much larger than the original amount invested.

Why the Multiplier Matters

The significance of the investment multiplier lies in its ability to illustrate how small actions can lead to large-scale results. Governments often rely on this principle when designing policies aimed at stimulating growth during economic slowdowns. For instance, funding infrastructure projects can create jobs, raise wages, and increase demand across multiple industries. Private investments work in a similar way, with spending on factories, technology, or research creating benefits that ripple outward.

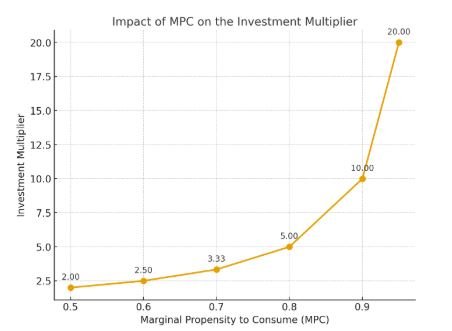

The size of the multiplier effect depends largely on two factors: the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) and the marginal propensity to save (MPS). These terms describe how much of each additional dollar a person spends or saves. A higher MPC means people spend more, resulting in a stronger multiplier effect.

How Spending Multiplies Across the Economy

To see the multiplier in action, consider the example of a government deciding to build a new highway. The construction company hired for the job pays wages to workers and purchases materials from suppliers. The workers then use their wages to buy food, pay rent, or purchase clothing. Suppliers, in turn, pay their employees and restock goods. Each transaction passes money along to others, spreading the economic benefit throughout different sectors.

This process does not continue forever, of course. At each stage, some portion of income is saved rather than spent, which slows down the cycle. Still, the overall result is a noticeable increase in economic activity that is several times larger than the original government investment.

The Role of MPC and MPS

The speed and strength of this cycle are determined by how much people tend to consume versus how much they save. If individuals spend 80% of their additional income and save 20%, the flow of money through the economy is faster and more powerful. On the other hand, if most of the money is saved instead of spent, the multiplier effect becomes weaker.

This relationship is expressed mathematically through a simple formula:

Investment Multiplier = 1 / (1 – MPC)

Because MPC and MPS always add up to 1, the formula can also be written as:

Investment Multiplier = 1 / MPS

Both versions highlight the same principle: the more people spend, the bigger the ripple effect on the economy.

Practical Example of the Multiplier

Imagine a construction worker earning $1,000 from a new infrastructure project. If their MPC is 70%, they spend $700 and save $300. That $700 might go to a local grocery store, which uses it to pay employees and buy inventory. The employees then spend part of their wages, perhaps on transportation or entertainment. Each round of spending is smaller than the previous one, but the combined impact adds up.

For businesses, the numbers can be even more striking. Suppose a company spends 90% of its income on operating costs like wages, raw materials, and services, keeping just 10% as profit. With an MPC of 0.9, the multiplier is 10, meaning every $1 of investment could eventually generate $10 in economic activity.

The Formula in Action

Using the multiplier formula makes it easier to see how small changes in spending habits can shift economic outcomes. For example:

- If MPC = 0.6, then Multiplier = 1 / (1 – 0.6) = 2.5

- If MPC = 0.8, then Multiplier = 1 / (1 – 0.8) = 5

- If MPC = 0.9, then Multiplier = 1 / (1 – 0.9) = 10

This explains why policymakers often focus on boosting consumer spending during recessions. When people are willing to spend more of their income, the same level of investment generates much stronger growth.

Keynes and the Origins of the Multiplier

The concept of the investment multiplier was popularized by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s during the Great Depression. His influential book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, reshaped modern economics by challenging the idea that markets naturally correct themselves. Keynes argued that active government intervention was sometimes necessary to revive demand and prevent prolonged economic downturns.

The multiplier became central to Keynesian economics, providing a theoretical framework for stimulus spending. It offered a way to justify policies where governments increase public investment during hard times to jumpstart growth and reduce unemployment.

Other Types of Multipliers

While the investment multiplier is one of the most well-known, it is not the only type of multiplier used in economics. Others include:

- Fiscal multiplier, which measures the effect of government taxation and spending on the economy.

- Earnings multiplier, often used in stock analysis to assess company value.

- Equity multiplier, a financial ratio that looks at how much a company relies on debt financing relative to equity.

Each of these multipliers serves a different purpose, but they all share the idea that an initial change can produce larger overall effects.

Why the Multiplier Still Matters Today

Even decades after Keynes first introduced the concept, the investment multiplier remains a central part of economic thought. It helps governments, businesses, and investors understand how spending decisions shape broader outcomes. For policymakers, it guides choices about stimulus packages, infrastructure funding, and tax policies. For businesses, it illustrates how investments in new projects not only improve their own operations but also strengthen the wider economy.

The multiplier also highlights the importance of consumer confidence. If people are uncertain about the future and prefer to save rather than spend, the chain reaction weakens. Conversely, when optimism is high and spending increases, the economy experiences stronger growth.

Final Thoughts

The investment multiplier provides a window into the interconnected nature of modern economies. A single decision to invest, whether in roads, factories, or technology, can create a ripple effect that benefits countless others. Understanding how marginal propensities to consume and save shape this process helps explain why some investments have more far-reaching consequences than others.

By capturing the idea that money in motion multiplies, the concept continues to influence economic policy and decision-making. It reminds us that no investment stands alone—each one sparks a chain of activity that spreads opportunity, income, and growth across society.

Major Facts

Investment Multiplier Shows Spending Ripple Effect

The investment multiplier explains how one round of spending creates further rounds of income and expenditure across the economy.

Rooted in Keynesian Economics

John Maynard Keynes introduced this idea in the 1930s, showing how investments can spark economic growth during downturns.

Links to Marginal Propensity to Consume

The size of the multiplier depends on how much of extra income people spend versus save, measured by MPC and MPS.

Higher MPC Means Stronger Impact

When households spend most of their additional income, the multiplier effect is larger, creating stronger economic stimulation.

Infrastructure Spending as an Example

Projects like road construction don’t just employ workers—they also increase demand for suppliers, retailers, and service providers.

Businesses Contribute to the Cycle

Companies, like households, spend much of their income on wages, rent, and expenses, further fueling the multiplier effect.

Simple Formula to Calculate It

The formula 1 ÷ (1 − MPC) makes it easy to see how spending habits directly affect the strength of the multiplier.

Not All Multipliers Are the Same

Other economic multipliers include fiscal multipliers, earnings multipliers, and equity multipliers, each measuring different effects.

A Tool for Policy Decisions

Governments use the investment multiplier to predict how spending programs can stimulate growth and shape economic strategy.