What is a W-Shaped Recovery?

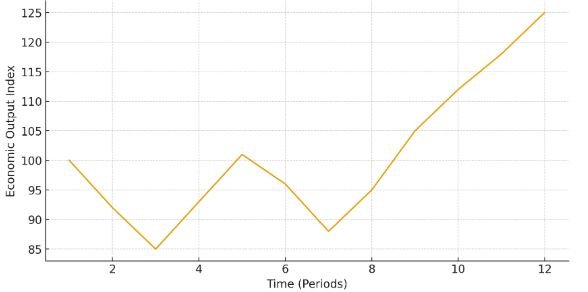

A W-shaped recovery describes an economic scenario in which a country or region falls into recession, begins to recover, slips back into another downturn, and then finally returns to stable growth. Instead of a single, continuous rebound, the recovery unfolds in alternating waves of contraction and expansion that collectively form a W-like pattern on charts tracking major economic indicators such as output, employment, and gross domestic product.

Economists often identify a W-shaped recovery by observing rapid drops in industrial activity, followed by temporary improvement, then another sharp decline before the final sustained rebound. The volatility of this pattern makes it difficult for businesses, households, and policymakers to anticipate market conditions with confidence. In particular, the “middle dip” of the W carries significant implications: it typically reflects a second economic shock or a failure of early recovery policies to support long-term stability.

Key Characteristics of a W-Shaped Recovery

A hallmark of this recovery pattern is its unpredictability. After the initial recession, the economy appears to rebound with encouraging momentum. Businesses hire again, consumer demand rises, and markets show renewed optimism. But this revival often proves temporary when structural weaknesses, global disruptions, or policy missteps trigger another downturn. The second contraction can be more severe because consumers and investors, who were already recovering from the first crisis, are once again thrust into uncertainty.

Tracking such a cycle requires careful analysis of multiple metrics, including industrial capacity utilization, retail sales, unemployment rates, and national income levels. Analysts also pay close attention to confidence indices, as shifts in sentiment often foreshadow the second decline. While the upward surges may briefly inspire hope, it is the double-dip trajectory that ultimately defines and differentiates a W-shaped recovery from V- or U-shaped alternatives.

Why the Middle Section Matters

The central portion of the W is particularly important because it exposes whether early government interventions were sufficiently robust. After the first rebound, policymakers may assume that the worst is over, reducing stimulus measures or adjusting interest rates prematurely. If underlying structural issues remain unresolved—such as weak banking systems, fragile supply chains, or high public debt—the economy becomes vulnerable to a second downturn.

The middle dip thus serves as a stress test of economic resilience. It reveals how markets react when early optimism collides with remaining vulnerabilities. In many cases, governments must modify or completely overhaul their initial strategies, deploying new rounds of fiscal support, monetary adjustments, or sector-specific relief packages. The effectiveness of these interventions largely determines how strongly the economy performs in the final upward movement of the W.

Understanding the Dynamics of W-Shaped Recoveries

Compared to other recovery shapes, a W-pattern is among the most disruptive. A V-shaped recovery signals a quick rebound after a sharp decline. A U-shaped recovery implies a longer recession before gradual improvement. An L-shaped pattern describes a severe downturn with prolonged stagnation. In contrast, a W involves repeated cycles—two recessions within a relatively short period—which destabilize both short-term and long-term planning.

This volatility is sometimes referred to as a “double-dip recession,” emphasizing the return to negative growth after an initial recovery. Economies going through this process often see fluctuations in currency values, erratic movements in stock markets, and inconsistent employment gains. Businesses that interpret the first rebound as the beginning of a stable recovery may expand too quickly, only to face losses during the second downturn.

An illustrative modern example occurred in the Americas during the early 2020s. Several Latin American countries, including Chile and Colombia, experienced a temporary economic resurgence after pandemic-related lockdowns were lifted. Investment inflows increased, mining output picked up, and consumer spending surged. However, global supply bottlenecks and inflationary pressures soon triggered another contraction. The second decline erased many early gains and forced governments to intervene with new budgetary and monetary measures to stabilize their economies.

The double-dip nature of W-shaped recoveries therefore affects all sides of economic life. Households face recurring job insecurity, lenders struggle with rising default risks, and capital markets become hesitant in allocating long-term investments.

New Historical Examples of W-Shaped Recovery

The East African Energy Shock (late 1990s)

A less frequently cited but relevant historical example emerged in East Africa during the late 1990s. Tanzania and Kenya experienced rapid expansion when international donors injected significant funding into infrastructure and energy development. GDP growth spiked, leading observers to predict a sustained boom.

However, a regional drought caused major hydroelectric shortages that halted industrial production. As factories shut down and food imports increased, inflation rose sharply. The economies contracted again before gradually stabilizing after new geothermal and natural gas facilities came online. This double-dip trajectory mirrored the defining features of a W-shaped recovery.

The Nordic IT Bubble and Housing Strain (early 2000s)

In the early 2000s, countries like Denmark and Finland also displayed a W-shaped pattern. Initially, they rebounded from the dot-com crash with strong tech-sector performance. But the quick rebound inflated housing markets and pushed household debt to unsustainable levels. When interest rates climbed and housing prices corrected, the economies experienced a second downturn. Only after financial reforms and tighter lending rules took effect did the region achieve stable long-term growth.

The South American Export Double Shock (mid-2010s)

Brazil and Peru encountered a W-shaped pattern during the mid-2010s as well. Commodity prices for copper, soybeans, and crude oil fell sharply, triggering an initial recession. A rebound followed when global demand briefly strengthened, pushing export revenues upward. But when China reduced its import volumes, the region slipped back into recession. Ultimately, targeted industrial policies and diversification strategies enabled these countries to regain momentum by the end of the decade.

These cases illustrate that W-shaped recoveries can appear in vastly different economic environments—from energy-dependent regions to export-driven and innovation-led economies. The unifying thread is the presence of two distinct downturns that interrupt the recovery path.

Implications for Businesses, Investors, and Policymakers

A W-shaped recovery is among the most challenging environments for investment and business planning. The initial recovery can entice firms to rehire, expand operations, and take on new financing. But when the second downturn arrives, these commitments can expose companies to heightened financial risk. Investors who allocate capital early in the first rebound may face steep losses during the subsequent contraction.

Governments and central banks also face challenges. They must strike a delicate balance between stimulating the economy and preventing inflation, asset bubbles, or excessive public debt. Premature withdrawal of support can contribute to the second downturn, while overly aggressive intervention can damage fiscal stability. Effective policy in a W-shaped recovery requires ongoing monitoring, scenario planning, and a willingness to adjust strategies rapidly.

Why W-Shaped Recoveries Are Considered Undesirable

The unpredictable oscillation between recession and recovery makes long-term decision-making difficult for virtually all economic participants. For businesses and investors, the risk of misreading early signs of revival can lead to costly misallocations of capital. For households, repeated layoffs or wage reductions strain financial security and consumer confidence. For policymakers, a W-shaped pattern highlights inefficiencies in crisis response and exposes structural vulnerabilities that were not fully addressed after the initial recession.

Because of these challenges, economists generally view W-shaped recoveries as suboptimal. They often signal that initial policy actions were incomplete or misaligned with broader economic realities.

Preferred Alternatives: V-Shaped or Hockey-Stick Recoveries

In contrast, a V-shaped recovery—or the increasingly referenced “hockey-stick” recovery—demonstrates strong resilience. After a sharp decline, the economy rebounds quickly and consistently, restoring production, employment, and financial stability in a relatively short time frame. These patterns indicate that underlying economic fundamentals remain sound and that policy interventions were timely and effective.

For these reasons, governments typically aim to avoid the double-dip scenario. Effective crisis management, structural reforms, targeted stimulus, and coordinated regulatory actions are essential for preventing the economy from slipping back into recession once early signs of recovery emerge.

W-Shaped Recovery – FAQs

What exactly is a W-shaped recovery?

A W-shaped recovery describes an economic pattern where the economy falls into recession, recovers briefly, slips back into another downturn, and then finally stabilizes. The sequence of decline, rebound, decline, and final rebound forms a shape resembling the letter W.

Why is the middle dip of the W so important?

The middle dip shows whether the first recovery was genuinely sustainable or simply a temporary rebound. It highlights underlying weaknesses or policy missteps that were not addressed the first time around and reveals how resilient the economy truly is.

How does a W-shaped recovery affect businesses?

Businesses often misinterpret the first rebound as a green light to expand, hire, or invest. When the second downturn hits, firms can be caught off guard, facing financial stress, shrinking demand, and reduced cash flow.

Why is this recovery path challenging for investors?

Investors who enter the market during the first upswing may see strong short-term gains. However, the second recession can quickly erase those gains. The volatility makes long-term planning and portfolio positioning more difficult.

What economic indicators signal a W-shaped pattern?

Analysts track metrics such as GDP, industrial output, unemployment rates, consumer confidence, and retail sales. Sudden surges followed by sharp declines across multiple indicators often reveal a double-dip recession.

How do governments contribute to a second downturn?

Governments may withdraw stimulus too early or tighten monetary policy too quickly after the first recovery. If structural issues remain unresolved, the economy becomes vulnerable to another recession.

Can you give an example of a modern W-shaped recovery?

Several Latin American economies experienced a W-pattern during the early 2020s. After the first pandemic-related rebound, rising inflation and global supply disruptions triggered a second contraction, erasing early progress.

Why are W-shaped recoveries considered undesirable?

They create repeated uncertainty, weaken consumer confidence, disrupt business planning, and increase the financial burden on governments. Two recessions in a short period intensify economic stress for households and firms.

What alternatives do economists prefer?

Economists favor V-shaped or hockey-stick recoveries. These patterns represent a sharp decline followed by sustained growth, indicating strong fundamentals and effective crisis response.

What lessons do policymakers learn from W-shaped recoveries?

They learn that early optimism can be misleading, and that maintaining flexible, well-timed policies is crucial. Structural reforms, targeted relief, and clear communication help prevent the economy from slipping back into recession.