Introduction to the Long Economic Wave Concept

For more than a century, economists, historians, and analysts have attempted to understand why modern economies experience long stretches of prosperity followed by equally long periods of slowdown. One of the most debated explanations is the idea of Kondratiev waves, a term used to describe long-term economic cycles that appear to unfold across several decades. These cycles, often lasting between forty and sixty years, are thought to be driven by major technological breakthroughs, shifts in production systems, societal changes, and credit conditions. Although mainstream economists remain divided about whether such long cycles truly exist, the concept continues to influence innovation studies, economic forecasting, and discussions about historical development.

Origins of the Kondratiev Wave Theory

The theory traces back to Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev, who in the 1920s examined long-term data on agricultural and industrial prices across Europe. By analyzing nearly 150 years of historical price records, he observed patterns that he believed formed long economic waves. These waves included extended stretches of rising prices and investment activity, followed by long periods of stagnation or decline. Kondratiev identified two major waves from 1790 to 1896 and proposed that a third one had already begun by the end of the 19th century.

Kondratiev’s conclusions were controversial in the Soviet Union. His findings suggested that capitalist economies experienced renewal rather than inevitable collapse, contradicting the ideological positions of the Stalinist government. His support for the New Economic Policy and market-based reforms further deepened political conflict, ultimately leading to his imprisonment and execution. Despite his tragic fate, his work continued to attract interest outside the Soviet Union.

Influential Thinkers Who Expanded the Theory

Following Kondratiev’s death, several economists and historians explored similar ideas. Joseph Schumpeter popularized the term “Kondratieff waves” and framed the cycles around clusters of transformative innovations that reshape industries. Earlier Dutch economists such as Jacob van Gelderen and Salomon de Wolff had already identified long cycles, but it was Schumpeter who connected them explicitly to technological revolutions such as steam engines, steel production, and rail transport.

Throughout the 20th century, the idea resurfaced repeatedly. Ernest Mandel tied long waves to the influences of war, global political shifts, and the rhythms of capitalism. Later, researchers such as George Modelski and William R. Thompson extended the study of long cycles beyond Europe, tracing them back nearly a thousand years in China. Other scholars examined commodity markets, interest rates, or demographic changes to identify long patterns in economic life.

Key Phases Within a Long Wave

Although interpretations differ, most descriptions of the long wave divide it into phases. Kondratiev originally identified expansion, stagnation, and recession, but many analysts prefer a four-stage model. Under this approach, a wave begins with a surge of new technologies that gradually spread across industries. As investment accelerates, productivity rises and economic activity expands. Eventually, the system reaches a point of overheating or diminishing returns, leading to slower growth and ultimately a downturn. This long downturn then sets the stage for institutional reforms and the next wave of innovation.

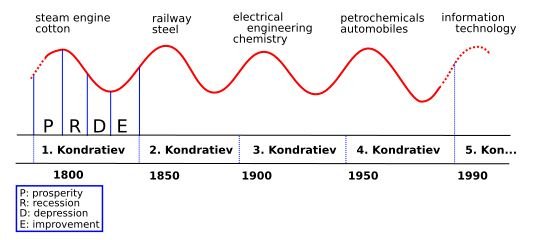

Historical examples illustrate this pattern. Kondratiev associated the first observed wave with the economic transformations following the late 18th century, and the second with the rise of steelmaking, railroads, and heavy manufacturing in the 19th century. Each wave brought new industries and energy sources, reshaping global production.

Technology as a Driver of Long-Term Change

One of the most widely discussed explanations for these long cycles is technological innovation. According to this view, major breakthroughs do not emerge evenly over time. Instead, they cluster in bursts, forming technological revolutions that drive productivity and reshape society. Examples include the steam age, the rise of electricity, the spread of automobiles, and later the information technology era.

Carlota Perez expanded this idea by placing these revolutions on a logistic curve. In her interpretation, a new technological era begins with an irruption phase, where experimental technologies emerge. This period is often chaotic, marked by speculative investment. As the technology becomes more widespread, a synergy phase emerges in which institutions adapt and productivity rises. Eventually, the system matures and stabilizes, completing the cycle and preparing the ground for the next transformation.

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, along with scholars like Mensch, Tylecote, Korotayev, and Ayres, developed various models that examine how long waves correspond to shifts in industrial sectors, infrastructure development, and energy use.

Demographics and Spending Patterns

Another explanation examines long-term demographic shifts. Because most people follow predictable spending patterns as they move through life stages—education, marriage, home buying, peak income years, and retirement—large demographic fluctuations can influence economic trends over decades. Baby booms and busts can create waves of increased consumption followed by lower demand. Analysts like Harry Dent and others have argued that major demographic cycles align with long-term economic expansions and contractions.

Influence of Land Markets and Speculation

A separate school of thought, rooted in Georgist economics, argues that land speculation is a major driver of long-term cycles. Because land is a finite and essential resource, cycles of rising land values and debt accumulation can create bubbles that eventually burst. Scholars such as Mason Gaffney, Fred Foldvary, and Fred Harrison have shown recurring patterns where access to credit and speculative investment amplify boom-and-bust cycles. Some Georgists even predicted the 2008 financial crisis well in advance, arguing that it reflected the end of a long speculative cycle.

Debt, Credit, and Financial Dynamics

Debt deflation theory, originally introduced by Irving Fisher after the Great Depression, holds that cycles of credit expansion and contraction can shape long-term economic trends. As debt accumulates, economies may experience booms, but once borrowers struggle to repay, widespread deleveraging can trigger economic collapse. The theory was overshadowed for decades by Keynesian ideas, but scholars like Hyman Minsky and Steve Keen revived interest by connecting long financial cycles to systemic instability.

Modern Variations and Technological Eras

Contemporary researchers have refined Kondratiev’s model by linking long waves to specific technological eras. These waves include the Industrial Revolution, the steam and railway age, the steel and heavy engineering era, the automobile and mass-production era, and the information and telecommunications wave beginning in the early 1970s. Some analysts believe a new wave is emerging, possibly driven by biotechnology, health innovation, or renewable energy.

Work by researchers such as Grübler and Marchetti charts the diffusion of major infrastructures—canals, railroads, highways—and finds that their peaks follow rhythms roughly aligned with long-wave lengths. Daniel Šmihula proposed another structure of six major innovation-driven waves since the 1600s, with each new wave slightly shorter than the one before. He argued that economic stagnation occurs when a technological system reaches its limits, and recovery follows when a new breakthrough emerges.

Understanding the Data and Statistical Controversy

Despite its popularity in innovation studies, the long-wave concept remains controversial. Many economists argue that the patterns identified by Kondratiev and others result from a statistical illusion. When raw data is heavily smoothed using moving averages or rates of change, it can create artificial cycles that appear meaningful but stem from the transformation process itself. This phenomenon, known as the Slutsky–Yule effect, demonstrates how random data can take on a wave-like appearance after repeated smoothing.

Critics also argue that the limited number of long cycles observable in modern data makes definitive conclusions impossible. Because only a few full waves could be analyzed, assigning precise start and end dates becomes subjective. Even among supporters of the theory, there is little agreement on how to identify the true boundaries of each wave.

Why the Theory Still Matters

Although the empirical validity of Kondratiev waves remains debated, the concept continues to influence how analysts interpret large-scale economic change. Investors sometimes use the theory to anticipate major shifts in markets, while policymakers and futurists look to long-wave thinking to understand how society responds to disruptive technologies. Historians also find value in mapping broad patterns that link technological breakthroughs to structural economic changes.

Conclusion

Kondratiev waves remain one of the most intriguing attempts to understand long-term economic evolution. Whether viewed as genuine cycles or as helpful metaphors for deeper structural changes, the theory highlights the powerful impact of innovation, demographic shifts, credit cycles, and societal transformation. While economists continue to debate the validity of long waves, the idea has shaped decades of discussion about how economies grow, adapt, and renew themselves through time.

Frequently Asked Questions about Kondratiev Waves

Why Did Kondratiev Develop This Theory?

Nikolai Kondratiev studied 150 years of economic data and noticed recurring long-term patterns in prices, production, and investment. He concluded that capitalist economies regularly renew themselves through waves of innovation rather than collapsing.

How Did Politics Affect Kondratiev’s Work?

His theory contradicted Soviet ideology, which claimed capitalism was destined to fail. Because his findings suggested renewal instead of collapse, he was persecuted, imprisoned, and later executed. His ideas survived only because Western scholars continued the research.

How Did Later Economists Expand His Theory?

Economists like Joseph Schumpeter connected long waves to clusters of major innovations—like steam power or electricity—that transform industries. Other thinkers added political, demographic, and global historical perspectives to broaden the model.

What Are the Main Phases of a Long Wave?

Most interpretations describe four stages: an innovation-driven expansion, a period of rising investment and productivity, a slowdown as the system matures, and a downturn that eventually prepares the economy for the next technological breakthrough.

How Does Technology Trigger Long Waves?

Major innovations don’t appear evenly over time—they come in powerful clusters. These breakthroughs spark new industries, attract investment, reshape society, and eventually form the backbone of a new economic era, such as the automobile age or the digital revolution.

What Role Do Demographics Play in These Cycles?

Large generations tend to follow predictable spending patterns—from education to home buying to retirement. These waves in consumer demand can reinforce long-term expansions or contribute to decades of slower growth when populations shrink or age.

How Does Land Speculation Influence Economic Cycles?

Some analysts argue that rising land prices and credit-fueled speculation create long booms that eventually burst. Because land is finite and essential, its cycles can ripple through the entire economy, as seen in past property bubbles.

What Do Debt and Credit Have To Do With Long Waves?

According to thinkers like Fisher and Minsky, long periods of easy credit encourage borrowing and investment, but when debt becomes overwhelming, deleveraging can trigger long downturns. These financial cycles often overlap with technological waves.

What Modern Waves Do Experts Recognize Today?

Researchers identify several major waves: the Industrial Revolution, steam and railways, steel and heavy engineering, automobiles and mass production, and the information technology era. Some believe a new wave—possibly centered on biotech or clean energy—is starting now.

Why Is the Theory Still Debated?

Critics argue that smoothing economic data can create “false” cycles, making patterns appear more meaningful than they are. Because only a few long waves exist in modern history, proving their timing or cause is difficult and often subjective.

Why Do People Still Study Kondratiev Waves Today?

Even if not perfect, the theory helps people think about how big innovations, demographic changes, and financial systems shape long-term economic evolution. Policymakers, investors, and futurists use it to understand where major shifts in global development may be heading.