One of the most influential contributions to modern economics was John Maynard Keynes’ explanation of how people spend and save. He introduced the consumption function, a concept that maps out the connection between income and household spending. By analyzing this relationship, economists can better predict economic activity and design policies to stabilize growth. Although later thinkers modified Keynes’ ideas, his framework remains a cornerstone of macroeconomic analysis.

The Basic Idea of the Consumption Function

At its core, the consumption function describes how much of a nation’s total income is spent on goods and services. Keynes argued that as income rises, spending also rises, but not at the same pace. People typically save a portion of their additional earnings, meaning consumption grows more slowly than income.

This concept became central to Keynesian economics, which emphasizes demand as a driver of growth. If consumer spending falters, economic activity contracts. On the other hand, when households spend more, businesses expand, jobs multiply, and growth accelerates.

Why Keynes Introduced the Concept

During the Great Depression, Keynes wanted to understand why economies sometimes spiral downward despite the availability of resources and labor. He realized that consumer spending patterns were a major piece of the puzzle. If people cut back on spending, businesses earned less, laid off workers, and the cycle worsened. The consumption function provided a way to link household behavior with national outcomes, giving policymakers a tool to fight recessions.

The Formula of the Consumption Function

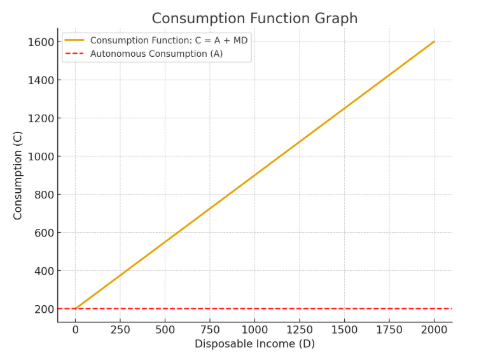

Keynes presented a relatively simple formula to represent spending behavior:

C = A + MD

- C represents total consumption.

- A stands for autonomous consumption—the baseline level of spending that happens even if income is zero, such as essential food, shelter, or clothing.

- M is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), which shows the fraction of additional income that people spend instead of saving.

- D is real disposable income, meaning the money households actually have after taxes and transfers.

This equation gave economists a straightforward way to predict how changes in income levels could influence national spending and overall demand.

Assumptions Behind the Model

Keynes assumed that the relationship between income and spending is fairly stable, at least in the short run. He suggested that most households would spend a predictable share of their income while saving the rest. This assumption allowed policymakers to use the formula when planning interventions such as tax cuts or stimulus packages.

However, Keynes also acknowledged that the function was a simplification. Spending patterns are shaped by more than just income—they can be influenced by wealth distribution, expectations about the future, or cultural attitudes toward saving.

Implications for Economic Policy

The consumption function had powerful implications for governments. Keynes argued that during downturns, consumer spending may not recover on its own. To prevent deep recessions, governments could step in by increasing public spending or cutting taxes, boosting demand until the private sector regained strength.

This approach was revolutionary at the time. It suggested that markets were not self-correcting and that deliberate government action could stabilize economies. The concept influenced decades of fiscal and monetary policy and continues to shape debates on how best to manage economic crises.

The Multiplier Effect

One of the key insights tied to the consumption function is the multiplier effect. When households receive additional income and spend part of it, the money circulates through the economy, generating more income for others. For example, when someone buys groceries, the store earns revenue, employees are paid, and suppliers make sales—all of which lead to more spending.

The higher the marginal propensity to consume, the stronger the multiplier. If people spend most of their extra earnings, the boost to the economy is larger. If they save more, the effect is smaller.

Practical Look

Consider a household where the main earner receives a salary increase. Instead of spending the entire extra income, the family allocates part of it to daily expenses like food, transport, and utilities, while saving the rest for emergencies and future needs. Their higher spending supports local businesses, which then generate more income and employment in the community. This simple pattern reflects the consumption function: as income rises, consumption increases, but usually by a smaller proportion.

Limitations of the Original Model

While the consumption function provided valuable insights, it soon became clear that its predictions did not always align with reality. Income and spending patterns often shifted in ways that the model couldn’t explain. For instance, as societies became wealthier, people sometimes saved more than Keynes expected.

Another limitation was that the function treated spending as a static relationship with income, ignoring other dynamic factors like credit availability, interest rates, or social safety nets. Over time, economists introduced new variations of the model to address these shortcomings.

Modern Adaptations of the Consumption Function

Several economists expanded on Keynes’ work. Franco Modigliani’s life cycle hypothesis suggested that people make spending decisions based on their entire expected lifespan, not just their current income. Younger workers may borrow to spend more, middle-aged workers may save heavily, and retirees may draw down savings.

Milton Friedman offered the permanent income hypothesis, which argued that people base spending on their long-term average income rather than short-term fluctuations. If someone gets a temporary bonus, they may save most of it, but if their salary permanently rises, their spending will adjust upward.

These adaptations made the consumption function more realistic by acknowledging that individuals consider future income, wealth, and expectations when deciding how much to spend.

What Causes Shifts in the Consumption Function?

The consumption function can shift upward or downward depending on several factors:

- Income changes: When disposable income rises, spending generally increases, shifting the function upward.

- Wealth effects: Rising asset values, such as housing or stocks, can boost spending even without higher incomes.

- Confidence and expectations: Optimism about the economy often encourages higher spending, while pessimism leads to caution.

- Interest rates and credit access: Easy borrowing can encourage consumption, while tight credit conditions reduce it.

Understanding these shifts is critical for policymakers who want to anticipate or respond to changes in consumer behavior.

Why the Consumption Function Still Matters

Despite its simplifications, the consumption function remains a central tool in economics. It helps explain why recessions deepen when households reduce spending and why recovery often requires a coordinated boost in demand. It also highlights the interdependence between income, savings, and growth.

For governments, the function provides guidance on how tax policies, transfer programs, and public investment can influence the economy. For businesses, it offers clues about consumer behavior, helping them plan production, pricing, and investment decisions.

Critiques and Ongoing Debate

Critics argue that the consumption function relies too heavily on assumptions about stability. In practice, spending patterns can shift unpredictably due to technological change, global events, or shifts in wealth distribution. The financial crisis of 2008, for example, showed how quickly consumer confidence and spending could collapse.

Others note that the model is less effective in explaining differences across income groups. Wealthier households may save more of their earnings, while lower-income households may spend nearly all of theirs. A single national function may therefore hide important inequalities in spending behavior.

Despite these criticisms, the function remains a valuable reference point, especially when combined with modern theories that account for uncertainty, borrowing, and global influences.

The Broader Significance of Keynes’ Contribution

Keynes’ introduction of the consumption function was more than just a mathematical relationship. It was part of a broader shift in economic thinking—away from the idea that markets always self-correct and toward the belief that active policy is sometimes necessary to prevent instability.

This insight continues to shape debates today, from stimulus programs during recessions to discussions on income inequality and its effects on demand. By linking household decisions to national outcomes, Keynes gave economists and policymakers a powerful framework to understand and manage economies.

Take-home

The consumption function remains one of the most enduring concepts in economics. By connecting income to spending, it explains how households influence the broader economy and why shifts in behavior can spark cycles of growth or decline. While the original model has been revised and expanded, its central message—that consumption plays a critical role in driving economic activity—still holds true.

Modern variations that include life expectancy, credit access, and permanent income considerations have made the model more robust. Yet its essence is the same: income and spending are tightly linked, and understanding this relationship is key to managing economies effectively.

Whether used to forecast recessions, design fiscal policy, or interpret consumer confidence, the consumption function remains a vital tool. It reminds us that economic health ultimately depends not just on markets or governments, but on the everyday decisions of households about how much to spend and save.

FAQs about Consumption Function

Why did Keynes develop the consumption function idea?

Keynes wanted to explain why economies sometimes fall into downturns. He believed consumer spending was central to recovery and that governments could step in to boost demand.

How is the consumption function calculated?

The formula is C = A + MD, where C is total spending, A is basic consumption even without income, M is the share of extra income spent (marginal propensity to consume), and D is disposable income.

What assumptions does the model make?

It assumes spending habits remain stable in the short run, with households spending predictable portions of their income while saving the rest.

Why is the consumption function important for policy?

It helps governments understand how tax cuts, transfers, or spending programs influence demand and growth, especially during economic slowdowns.

What is the multiplier effect?

When people spend extra income, that money circulates, creating jobs and further spending. The higher the marginal propensity to consume, the stronger the multiplier.

What are some criticisms of the model?

Critics argue it oversimplifies reality by ignoring factors like credit, expectations, or wealth distribution, and that it doesn’t always match actual spending behavior.

How have economists updated Keynes’ idea?

Franco Modigliani added the life cycle theory, while Milton Friedman introduced the permanent income hypothesis—both showing that people consider future income and savings, not just current earnings.

Why does the consumption function still matter today?

It remains a vital tool for predicting economic activity, designing fiscal policies, and understanding how households’ decisions about spending and saving shape national growth.