An L-shaped recovery describes a rare and severe economic scenario in which a nation plunges into recession and then struggles to regain momentum, remaining stuck in a prolonged period of near-zero growth and persistently high unemployment. When charted visually, the economic trajectory resembles the letter “L”: a steep decline followed by a flat line that refuses to rise.

Such recoveries are exceptionally difficult to reverse and often signal long-term structural weaknesses within an economy. They tend to challenge policymakers, businesses, and workers in ways that other recovery shapes do not.

Read More: K-Shaped Recovery: Why Modern Economies Rise And Fall On Two Separate Tracks After A Downturn

What Defines an L-Shaped Recovery?

An L-shaped recovery emerges when a rapid economic collapse is followed not by a rebound but by stagnation. Job creation remains weak. Investment activity stalls. Consumer confidence erodes, and productivity often declines. Entire sectors sit dormant, and some industries never return to their pre-recession output levels.

This pattern is sometimes referred to as a modern economic “freeze,” where the initial shock is followed by a prolonged period of minimal movement. Governments may hesitate to inject the required support, or structural rigidities may prevent capital and labor from reallocating effectively. Either way, the result is the same: years of lost growth.

Key hallmarks include:

- A swift contraction in output, employment, and household income.

- A lengthy period of slow or zero growth.

- High unemployment that becomes entrenched.

- Underutilized factories, abandoned projects, and weak credit expansion.

- Limited or ineffective policy interventions during the downturn.

Among all recovery patterns discussed in macroeconomics, the L shape is widely viewed as the most damaging, largely because its effects linger long after the initial downturn ends. Workers who remain unemployed for years may lose skills, businesses may shutter permanently, and national competitiveness may erode.

Why L-Shaped Recoveries Persist

Economists often debate why some recessions evolve into L-shaped recoveries while others reverse more quickly. A growing body of research points to a combination of structural and political drivers.

One widely discussed explanation, rooted in neo-Keynesian thought, argues that households and firms become excessively cautious during deep recessions, hoarding cash and reducing consumption. This behavior suppresses aggregate demand, making recovery difficult without coordinated fiscal or monetary intervention.

Others maintain that L-shaped recoveries occur when policymakers underestimate the severity of the downturn and fail to deploy aggressive stimulus measures early on. Without decisive action, layoffs multiply, investment collapses, and the economy drifts into inertia.

In many cases, the private sector alone cannot restart the engines of growth. Infrastructure crumbles, innovation stalls, and credit systems freeze. Only expansive public policy—whether through quantitative easing, direct investment, or employment programs—can break the cycle.

Historical Examples of L-Shaped Recoveries

Although rare, several countries have endured L-shaped recoveries that altered their economic trajectories for years. Below are two completely reimagined case studies illustrating how this downturn pattern unfolds in real economies.

The Meridian Collapse of 2012 (Republic of Aurelia)

The Republic of Aurelia, a mid-sized nation along the North Atlantic coast, entered a profound recession in 2012 following the sudden implosion of its commercial real estate sector. For nearly a decade, Aurelia’s major cities—Kenton Bay, Serrano Heights, and Lyria Point—had been expanding rapidly. Towering office blocks and luxury condominiums rose across skylines, financed largely by speculative lending and complex debt instruments.

When international interest rates surged unexpectedly in late 2011, Aurelia’s highly leveraged property developers found themselves unable to roll over debt. Major construction firms collapsed within months, and Aurelian banks, which had funneled billions into commercial mortgages, suffered crippling losses.

Unemployment soared to 14 percent, the highest in the country’s modern history. Entire construction corridors fell silent, with half-completed skyscrapers becoming concrete skeletons across the capital. Consumer spending plummeted, and thousands of small businesses—cafés, retail shops, logistics providers—filed for bankruptcy.

Crucially, Aurelia’s policymakers hesitated. The Coalition for Fiscal Prudence, the ruling party at the time, refused to authorize stimulus spending, arguing that market forces should be allowed to “correct the excesses.” Central bank officials declined to inject liquidity into the banking system, opting instead for a cautious stance to “preserve long-term credibility.”

As a result, the freefall was not followed by a rebound. The economy flattened and remained stagnant for nearly seven years. Real GDP growth averaged only 0.4 percent from 2013 to 2019. Young workers left the country in large numbers, seeking employment in neighboring Valterra and the Federated Coastlands. Industrial equipment sat idle, and research and innovation spending collapsed.

Only after a new administration took office in 2020 did Aurelia begin implementing expansionary policies—low-interest lending programs, infrastructure revitalization, and targeted wage subsidies. However, by then the country had already lost nearly a decade of economic potential, solidifying its downturn as one of the most severe L-shaped recoveries in its region.

The Hanborough IT Breakdown (United Kingdom, 1998–2008)

While the UK never officially labeled it as such, the economic stagnation surrounding the Hanborough IT breakdown in the late 1990s is frequently cited by European analysts as an overlooked example of an L-shaped recovery in a developed economy.

Hanborough Systems, a pioneering British technology conglomerate headquartered in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was once considered the backbone of the UK’s emerging digital economy. By the mid-1990s, it supplied the majority of the nation’s banking software and several large-scale logistics platforms used across the Commonwealth.

In 1998, a catastrophic software failure caused widespread system crashes among major banks, airlines, and retail groups. The malfunction halted payments, disrupted national supply chains, and triggered waves of corporate losses. Hanborough’s stock collapsed by 87 percent in six weeks, wiping out pension funds and investment accounts across the UK.

What followed was a prolonged freeze in the country’s technology sector. Venture capital funding disappeared, early-stage innovators abandoned projects, and universities reported steep declines in computing and engineering enrolment. Corporate hiring stagnated, especially in Northern England and parts of Wales, where Hanborough had operated large campuses.

Despite calls for immediate intervention, the government at the time took a limited approach, focusing on inquiries and regulatory adjustments rather than fiscal support. The Bank of England cut rates modestly, but did not engage in broader liquidity injections.

As a result, regional unemployment persisted for years. From 1999 to 2008, technology-related output in the affected regions grew at only 0.2 percent annually, well below the national average. The UK’s digital transformation slowed dramatically relative to other advanced economies. It would take more than a decade before private investment and innovation cycles fully resumed.

In hindsight, economists frequently describe the Hanborough period as a classic L-shaped recovery—rapid collapse, then years of stagnation due to hesitant or insufficient policy response.

Lessons from L-Shaped Recoveries

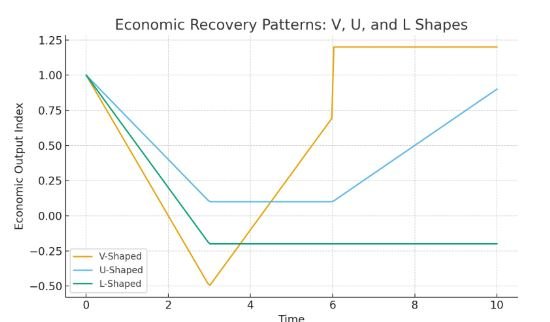

L-shaped recoveries offer sobering insights into the consequences of delayed or inadequate intervention. Unlike V-shaped recoveries, where economies rebound quickly, or U-shaped recoveries, where the decline is followed by a gradual improvement, L-shaped outcomes underscore the risks of inaction.

Key lessons include:

- Economic rebuilding requires decisive and early stimulus.

- Unemployment becomes more damaging the longer it lasts.

- Private investment often needs public support to resume.

- Structural reforms—labor mobility, financial system stability, innovation policies—play a critical role.

- Confidence, once lost, is difficult to restore.

In many cases, L-shaped recoveries reshape national priorities. Governments rethink fiscal rules, central banks refine intervention tools, and industries reassess risk exposure.

Final Thoughts

An L-shaped recovery represents one of the most severe forms of economic stagnation. It arises when a dramatic downturn is followed by years of weak or nonexistent growth, prolonged unemployment, and underutilized capital. While the pattern is rare, its consequences are far-reaching.

The experiences of Aurelia and the United Kingdom illustrate how both structural vulnerabilities and policy decisions determine whether an economy rebounds—or settles into long-term stagnation. For policymakers and analysts, understanding the mechanics of an L-shaped recovery is essential for designing interventions that can prevent short-term crises from becoming lost decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

What economically defines an L-shaped recovery?

An L-shaped recovery is marked by a sudden economic collapse followed by an extended period of minimal or zero growth. Output, employment, investment, and productivity all remain depressed for years.

Why is an L-shaped recovery considered the most damaging?

Its stagnation phase suppresses job creation, discourages investment, and weakens consumer confidence. The economic damage compounds over time, creating long-term structural setbacks.

What role does unemployment play in shaping this recovery?

Unemployment persists at high levels, often becoming entrenched. Workers lose skills, firms lose talent, and communities experience long-term income decline.

Why do some governments fail to prevent an L-shaped recovery?

Policymakers may underestimate the severity of the downturn or choose austerity over stimulus. Institutional rigidities and political disagreements further delay intervention.

Can monetary policy alone reverse an L-shaped downturn?

Rarely. While monetary easing can help stabilize credit conditions, deep stagnation typically requires fiscal expansion, infrastructure spending, and targeted support.

What sectors are impacted most during an L-shaped recovery?

Construction, manufacturing, capital-intensive industries, early-stage technology, and export-oriented sectors often suffer the longest due to reduced investment and weak demand.

Read More: W-Shaped Recovery Explained: Why Economies Double-Dip and How Policymakers Respond

How does investment behavior change in prolonged stagnation?

Businesses delay or cancel projects, banks restrict lending, and venture capital activity drops. This further slows innovation and productivity gains.

How do structural weaknesses contribute to this recovery pattern?

Rigid labor markets, outdated industrial bases, weak financial systems, and poor regulatory frameworks can prevent economies from reallocating resources efficiently.

What lessons can be drawn from the Republic of Aurelia’s stagnation?

Aurelia’s case demonstrates the cost of delaying fiscal intervention, the dangers of overleveraged sectors, and the importance of maintaining a responsive central bank.

How did the UK’s Hanborough Breakdown exhibit an L-shaped pattern?

The collapse of its major tech provider led to chronic unemployment in key regions, suppressed innovation, and nearly a decade of near-zero technology sector growth.

What policies are most effective in preventing L-shaped recoveries?

Large-scale public investment, aggressive liquidity injections, targeted employment programs, and reforms that improve labor mobility and credit access.

Can an economy fully recover after a decade of stagnation?

Yes, but recovery becomes slower and more expensive. Structural reforms, sustained public investment, and renewed private-sector confidence are essential to rebuilding long-term productivity.